---

config:

theme: neutral

---

flowchart LR

subgraph old [Old Way - Dedicated Wires N²]

direction TB

M1["A"]

M2["B"]

M3["C"]

M4["D"]

M5["E"]

M6["F"]

M7["G"]

M8["H"]

M1 -.-> M2

M1 -.-> M3

M1 -.-> M4

M1 -.-> M5

M1 -.-> M6

M1 -.-> M7

M1 -.-> M8

M2 -.-> M3

M2 -.-> M4

M2 -.-> M5

M2 -.-> M6

M2 -.-> M7

M2 -.-> M8

M3 -.-> M4

M3 -.-> M5

M3 -.-> M6

M3 -.-> M7

M3 -.-> M8

M4 -.-> M5

M4 -.-> M6

M4 -.-> M7

M4 -.-> M8

M5 -.-> M6

M5 -.-> M7

M5 -.-> M8

M6 -.-> M7

M6 -.-> M8

M7 -.-> M8

end

subgraph new [New Way - Packet Routing]

direction TB

SW1["Switch 1"]

SW2["Switch 2"]

Mod1["A<br/>addr"] --> SW1

Mod2["B<br/>addr"] --> SW1

Mod3["C<br/>addr"] --> SW1

Mod4["D<br/>addr"] --> SW1

Mod5["E<br/>addr"] --> SW2

Mod6["F<br/>addr"] --> SW2

Mod7["G<br/>addr"] --> SW2

Mod8["H<br/>addr"] --> SW2

SW1 <--> SW2

end

18 The ‘Route Packets, Not Wires’ Paper (2001)

18.1 Overview

This appendix reviews William J. Dally and Brian Towles’ seminal 2001 paper “Route Packets, Not Wires: On-Chip Interconnection Networks” from DAC 2001, which proposed a fundamental shift in how we think about interconnects at any scale.

For how this same pattern appears at NoC → PCIe → Datacenter scales, see Chapter 2: L3 & Routing Trends - Big Picture.

18.2 The Paper’s Core Proposal

The problem (2001): As chips grew denser with more modules (CPU cores, memory controllers, peripherals), connecting them with ad-hoc dedicated wiring became impractical. Design-specific global wiring was complex, unpredictable, and required extensive timing iterations.

The solution: Replace ad-hoc global wiring with a general-purpose on-chip packet network. System modules communicate by sending packets to one another over the network, not by dedicated wires.

This idea evolved into what we now call Network-on-Chip (NoC), which is common practice in modern SoCs. Most multi-core processors today (ARM, AMD, Intel, Apple Silicon) use NoC architectures rather than shared buses.

The architecture:

- Divide the chip into rectangular tiles

- Each tile contains a client module (processor, memory, etc.) and a small router

- Tiles communicate by sending packets with addresses

- Routers forward packets through a structured network

- Physical wiring is shared infrastructure, not module-specific

18.3 Key Technical Insights from the Paper

18.3.1 1. Structured Wiring Enables Better Circuits

From the paper: Structured network wiring gives “well-controlled electrical parameters that eliminate timing iterations and enable the use of high-performance circuits.”

Structured wiring enables better link circuits (the intuition):

When wires are laid out in a regular, predictable way (similar lengths, controlled spacing), we can design a “standard link” circuit (driver/receiver) once and replicate it everywhere. With ad-hoc global wiring, every long wire behaves differently due to coupling and RC effects, so designers add conservative safety margins and lots of repeaters.

What this enables:

- ~100× lower switching energy on the wire: A wire is basically a capacitor; toggling it means moving charge. If the signal swing is reduced from ~1.0V to ~0.1V, the wire’s switching energy drops with V², i.e., about 100× lower dynamic energy. (Total link power won’t drop 100× because drivers/receivers also consume power, but it’s still a major win.)

- Higher speed / lower delay: The “speedup” isn’t that electrons move faster; it’s that predictable wiring lets the receiver detect transitions sooner (less RC smearing, more controlled behavior), enabling higher clock rates or deeper pipelining.

- Fewer repeaters: With a well-behaved link, signals can travel farther before needing buffering, reducing repeater count (saving both area and power).

18.3.2 2. Identity Separate from Physical Location

Conceptual shift: Each module gets a stable network address (its “identity”), independent of physical location or which wires connect it.

This is the same principle as:

- On-chip: Tile address (not which physical wire)

- PCIe: Endpoint ID (not which motherboard slot)

- Datacenter: Loopback IP (not which NIC or ToR)

18.3.4 4. Modularity Through Standard Interface

From the paper: An on-chip network defines a standard interface “in much the same manner as a backplane bus.”

Modules designed for the standard interface are reusable and interoperable—you don’t need custom wiring for each new module combination.

At datacenter scale: BGP + /31 p2p links is our “standard interface.” Any host/ToR/spine speaking BGP can plug into the fabric. No custom per-rack wiring designs.

18.4 Why the Paper Matters for Our Design

Dally & Towles articulated principles that apply at every scale:

- Structure over ad-hoc: Hierarchical addressing, structured links beat custom wiring

- Identity ≠ connectivity: Loopback IPs (like tile addresses) are stable; physical links can change

- Shared infrastructure scales: ECMP uses all paths; dedicated pipes waste bandwidth

- Standard interfaces enable modularity: BGP everywhere (like packet interface everywhere) enables plug-and-play growth

Our datacenter design is the same pattern at building scale: replace L2 broadcast (ad-hoc wiring equivalent) with L3 routing (packet network equivalent).

18.5 The N² Problem

- First: Packet routing with 2 switches = 9 wires (4 to each switch + 1 inter-switch)

- Second: N² dedicated wires = 8×7÷2 = 28 dedicated wires for full connectivity

As N grows, dedicated wiring becomes impossible. Packet routing scales.

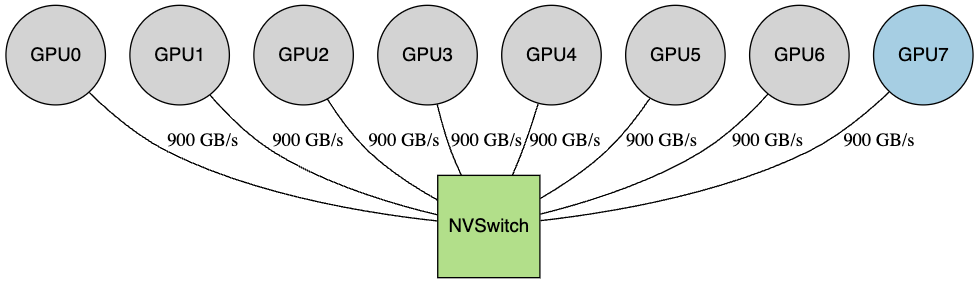

18.5.1 Modern Example: GPU Interconnects

This same tradeoff appears in modern GPU interconnects:

NVIDIA NVSwitch (routing approach):

- 8 GPUs each connect to NVSwitch fabric

- NVSwitch is not a single switch; it’s a fabric built from multiple NVSwitch ASICs (e.g., 4× on HGX H100/H200-class systems; exact count varies by generation)

- This is still a clean topology: it scales by adding switch ASICs, like the “packet routing” model from Dally’s paper

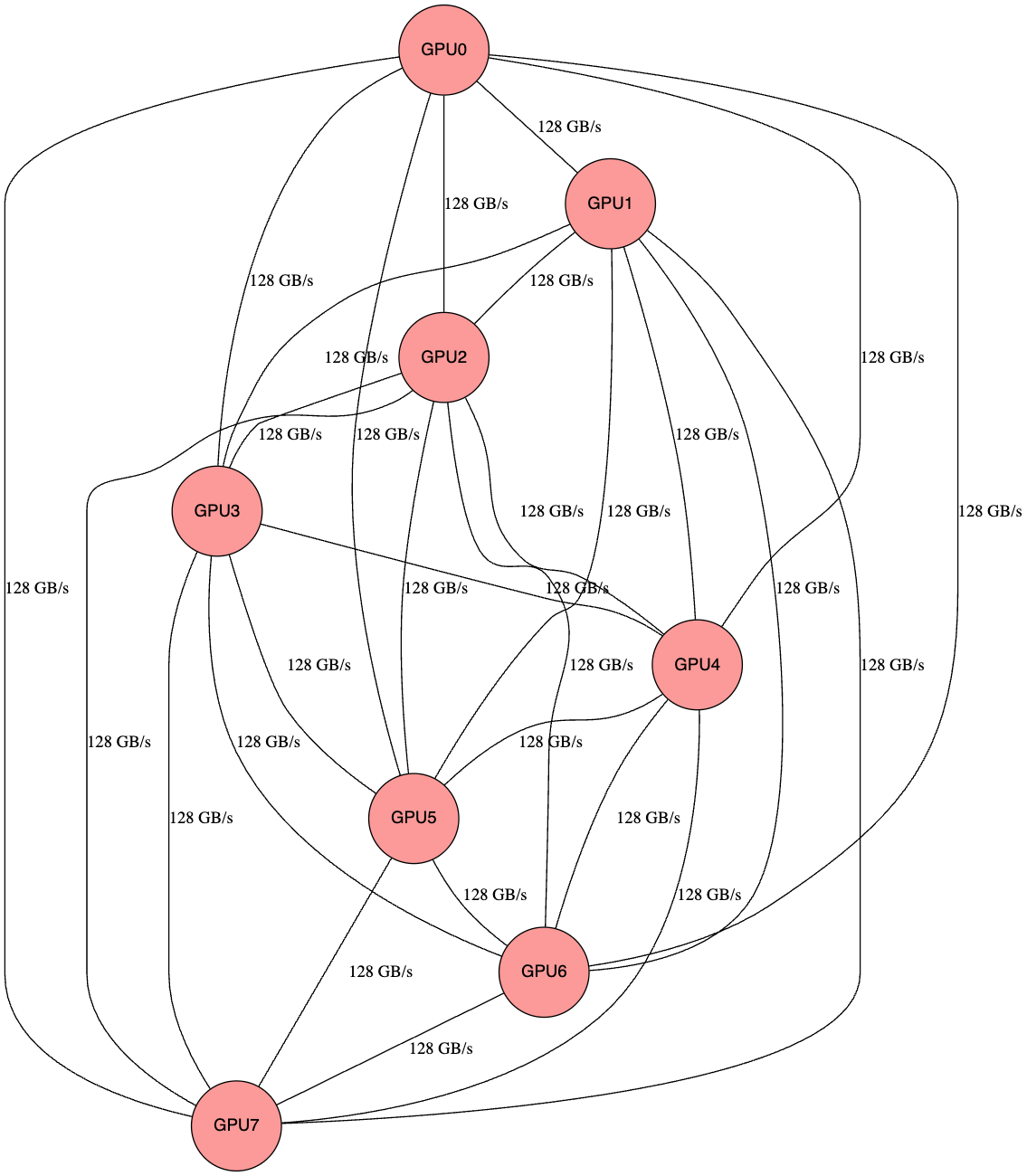

AMD Infinity Fabric Direct (P2P mesh approach):

- Each GPU directly connects to every other GPU with P2P connections

- 28 direct links for 8 GPUs (N² = 8×7÷2)

- Works well for small N (a single node), but the number of direct links grows as N², so scaling beyond 8 GPUs becomes impractical

18.6 Conclusion

“Route Packets, Not Wires” isn’t just about on-chip networks—it’s a universal principle for any communication system that needs to scale.

The same lesson applies to datacenters: Don’t dedicate VLANs and L2 paths. Route IP packets with BGP over structured /31 links. Give hosts stable loopback identities. Let ECMP share bandwidth.

This paper helped establish the mental model that guides modern datacenter network design.

18.7 References

- Dally, William J., and Towles, Brian. “Route Packets, Not Wires: On-Chip Interconnection Networks”. DAC 2001.

- Dally, William J., and Poulton, John W. “Digital Systems Engineering.” Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Seitz, Charles. “Let’s Route Packets Instead of Wires.” Advanced Research in VLSI: Proceedings of the Sixth MIT Conference, 1990.